Using the Status bar

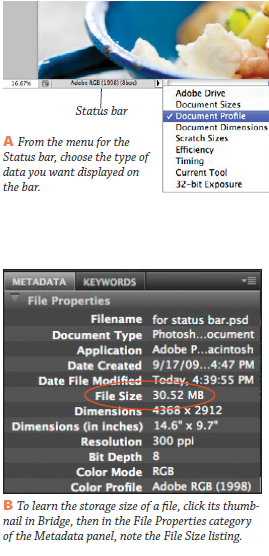

Using the Status bar and menu at the bottom of the document window, you can read data about the current fi le or fi nd out how Photoshop is currently using

memory.

To use the Status bar:

From the menu next to the Status bar at the bottom of a fl oating or tabbed document window,choose the type of data you want displayed on the bar:

Document Sizes to list the approximate fi le storage size of a fl attened version of the fi le if it were saved in the PSD format (the value on the left)and the storage size of the current fi le including layers (the value on the right).

Document Profi le to list the embedded color profi le (the words “Untagged [RGB or CMYK]”appear if a profi le hasn’t been assigned).A Document Dimensions to list the image dimensions (its width, height, and resolution).

Scratch Sizes to list the amount of RAM Photoshop is using to process all currently open fi les (the value on the left) and the amount of RAM that is currently available to Photoshop (the value on the right). If the fi rst value is greater

than the second, it means Photoshop is currently utilizing virtual memory on the scratch disk.

Effi ciency to list the percentage of program operations that are currently being done in RAM as opposed to the scratch disk (see page 391).

When this value is below 100, it means the scratch disk is being used.

Current Tool to list the name of the current tool.To view detailed data about a particular fi le, use the Metadata panel in Bridge.

To fi nd out the storage size (and other data)of a fi le:

1. On the Application bar in Photoshop, click the Bridge button. In Bridge, click an image thumbnail (see page 36).

2. In the Metadata panel on the right, under File Properties, note the File Size value.B

vendredi 25 novembre 2011

Saving your file

Saving your file

If you’re not sure which format to use when saving a fi le for the fi rst time, you can safely go with the native Photoshop format, PSD. One good reason to do so is that PSD fi les are more compact than TIFFfi les (see also the sidebar on the following page).

To save an unsaved document:

1. If the document window contains any imagery,you can choose File > Save (CtrlS/Cmd-S); if it’s completely blank, choose File > Save As (Ctrl- Shift-S/Cmd-Shift-S). Th e Save As dialog opens.

2. Type a name in the File Name fi eld A/Save As fi eld (A, next page).

3. Choose a location for the fi le.In Windows, if you need to navigate to a diff erent folder or drive, use the Save In menu at the top of the dialog.

In the Mac OS, click a drive or folder in the Sidebar panel on the left side of the window.

To locate a recently used folder, use the menu below the Save As fi eld.

4. Choose a fi le format from the Format menu.Only the native Photoshop (PSD), Large Document Format (PSB), TIFF, and Photoshop PDF formats support layers (see the information about fl attening layers on pages 134 and146).

5. If you’re not yet familiar with the features listed in the Save area, leave the settings as is.Th e As a Copy option is discussed on page 26.

6. If the fi le contains an embedded color profi le and the format you’re saving to supports such profi les, in the Color area, you can check ICC Profi le/Embed Color Profi le: [profi le name] to save the profi le with the fi le. (To learn about embedded profi les, see pages 10,

13, and 16.)

7. Click Save.

➤ In the Mac OS, to have Photoshop append a three-character extension (e.g., .tif, .psd) to the fi le name automatically when a fi le is saved for the fi rst time, in Edit/Photoshop > Preferences >File Handling, choose Append File Extension:

Always. Extensions are required when exportingMacintosh fi les to the Windows platform and when posting fi les to a Web server.

➤ To learn about the Maximize PSD and PSB File Compatibility option in the File Handling panel of the Preferences dialog,

Once a fi le has been saved for the fi rst time, each subsequent use of the Save command overwrites (saves over) the last version.

To save a previously saved fi le: Choose File > Save (Ctrl-S/Cmd-S).Th e simple Revert command restores your document to the last-saved version.

Note: We know you can’t learn everything at once,but keep in mind for the future that the History panel, which Chapter 10 is devoted exclusively to,serves as a full-service multiple undo feature. Also,a use of the Revert command shows up as a state on the History panel, so you can undo a revert by clicking an earlier history state.

To revert to the last saved version of a fi le: Choose File > Revert.

➤ To undo the most recent modifi cation, choose Edit > Undo (Ctrl-Z/Cmd-Z). Not all edits can be undone by this command. For the other undo

and redo commands

Th e Save As command lets you save a copy of your fi le under a new name (say, to create a design, document color mode, or adjustment variation) or with diff erent options. Another important use of this command is to save a fl attened copy of a fi le in a different format, for export to another application. Th is is necessary because most non-Adobe applications can’t import Photoshop PSD fi les or read Photoshop layers.

To save a new version of a fi le:

1. Choose File > Save As (Ctrl-Shift-S/Cmd- Shift-S). Th e Save As dialog opens.

2. Change the name in the File Name/Save As fi eld. Th is is important!

3. Choose a location for the new version fromnthe Save In menu in Windows or by using the Sidebar panel and columns in the Mac OS. (Read about the new Save As to Original Folder preference on page 390.★)

4. Optional: From the Format menu, choose a different fi le format. Only formats that are available for the fi le’s current color mode and bit depth are listed. Note: If you try to save a 16-bit fi le in the JPEG (.jpg) format, Photoshop will produce a fl attened, 8-bit copy of the fi le automatically.★ Beware! If the format you’ve chosen doesn’t support layers, the Layers option becomes dimmed, a yellow alert icon displays, and layers in the newversion are fl attened.

A DESIGNER’S BEST FRIEND To create document variations within the same fi le, explore the Layer Comps panel; see pages 382–384.

5. Check any available options in the Save area, as desired. For example, you could check As a Copy to have the copy of the fi le remain closed and the original fi le stay open onscreen, or uncheck this option to have the original fi le close and the

copy stay open.Depending on the current File Saving settings in Edit/Photoshop > Preferences > File Handling(and depending on whether you’re working on a Windows or Mac OS machine), some preview andextension options may be available in the Save As dialog. See pages 389–390.

6. In the Color area, check ICC Profi le/Embed Color Profi le: [profi le name], if available , to include the profi le, for color management.

7. Click Save. Depending on the chosen fi le format,another dialog may appear. For the TIFF format,see page 417; for EPS, see pages 418–419; orfor PDF, see page 420. For other formats, see Photoshop Help.

➤ If you don’t change the fi le name or format in the Save As dialog but do click Save, an alert will appear. Click Yes/Replace to replace the original fi le, or click No/Cancel to return to the Save As dialog.

➤ To optimize a fi le in the GIF or JPEG format for Web output,

If you’re not sure which format to use when saving a fi le for the fi rst time, you can safely go with the native Photoshop format, PSD. One good reason to do so is that PSD fi les are more compact than TIFFfi les (see also the sidebar on the following page).

To save an unsaved document:

1. If the document window contains any imagery,you can choose File > Save (CtrlS/Cmd-S); if it’s completely blank, choose File > Save As (Ctrl- Shift-S/Cmd-Shift-S). Th e Save As dialog opens.

2. Type a name in the File Name fi eld A/Save As fi eld (A, next page).

3. Choose a location for the fi le.In Windows, if you need to navigate to a diff erent folder or drive, use the Save In menu at the top of the dialog.

In the Mac OS, click a drive or folder in the Sidebar panel on the left side of the window.

To locate a recently used folder, use the menu below the Save As fi eld.

4. Choose a fi le format from the Format menu.Only the native Photoshop (PSD), Large Document Format (PSB), TIFF, and Photoshop PDF formats support layers (see the information about fl attening layers on pages 134 and146).

5. If you’re not yet familiar with the features listed in the Save area, leave the settings as is.Th e As a Copy option is discussed on page 26.

6. If the fi le contains an embedded color profi le and the format you’re saving to supports such profi les, in the Color area, you can check ICC Profi le/Embed Color Profi le: [profi le name] to save the profi le with the fi le. (To learn about embedded profi les, see pages 10,

13, and 16.)

7. Click Save.

➤ In the Mac OS, to have Photoshop append a three-character extension (e.g., .tif, .psd) to the fi le name automatically when a fi le is saved for the fi rst time, in Edit/Photoshop > Preferences >File Handling, choose Append File Extension:

Always. Extensions are required when exportingMacintosh fi les to the Windows platform and when posting fi les to a Web server.

➤ To learn about the Maximize PSD and PSB File Compatibility option in the File Handling panel of the Preferences dialog,

Once a fi le has been saved for the fi rst time, each subsequent use of the Save command overwrites (saves over) the last version.

To save a previously saved fi le: Choose File > Save (Ctrl-S/Cmd-S).Th e simple Revert command restores your document to the last-saved version.

Note: We know you can’t learn everything at once,but keep in mind for the future that the History panel, which Chapter 10 is devoted exclusively to,serves as a full-service multiple undo feature. Also,a use of the Revert command shows up as a state on the History panel, so you can undo a revert by clicking an earlier history state.

To revert to the last saved version of a fi le: Choose File > Revert.

➤ To undo the most recent modifi cation, choose Edit > Undo (Ctrl-Z/Cmd-Z). Not all edits can be undone by this command. For the other undo

and redo commands

Th e Save As command lets you save a copy of your fi le under a new name (say, to create a design, document color mode, or adjustment variation) or with diff erent options. Another important use of this command is to save a fl attened copy of a fi le in a different format, for export to another application. Th is is necessary because most non-Adobe applications can’t import Photoshop PSD fi les or read Photoshop layers.

To save a new version of a fi le:

1. Choose File > Save As (Ctrl-Shift-S/Cmd- Shift-S). Th e Save As dialog opens.

2. Change the name in the File Name/Save As fi eld. Th is is important!

3. Choose a location for the new version fromnthe Save In menu in Windows or by using the Sidebar panel and columns in the Mac OS. (Read about the new Save As to Original Folder preference on page 390.★)

4. Optional: From the Format menu, choose a different fi le format. Only formats that are available for the fi le’s current color mode and bit depth are listed. Note: If you try to save a 16-bit fi le in the JPEG (.jpg) format, Photoshop will produce a fl attened, 8-bit copy of the fi le automatically.★ Beware! If the format you’ve chosen doesn’t support layers, the Layers option becomes dimmed, a yellow alert icon displays, and layers in the newversion are fl attened.

A DESIGNER’S BEST FRIEND To create document variations within the same fi le, explore the Layer Comps panel; see pages 382–384.

5. Check any available options in the Save area, as desired. For example, you could check As a Copy to have the copy of the fi le remain closed and the original fi le stay open onscreen, or uncheck this option to have the original fi le close and the

copy stay open.Depending on the current File Saving settings in Edit/Photoshop > Preferences > File Handling(and depending on whether you’re working on a Windows or Mac OS machine), some preview andextension options may be available in the Save As dialog. See pages 389–390.

6. In the Color area, check ICC Profi le/Embed Color Profi le: [profi le name], if available , to include the profi le, for color management.

7. Click Save. Depending on the chosen fi le format,another dialog may appear. For the TIFF format,see page 417; for EPS, see pages 418–419; orfor PDF, see page 420. For other formats, see Photoshop Help.

➤ If you don’t change the fi le name or format in the Save As dialog but do click Save, an alert will appear. Click Yes/Replace to replace the original fi le, or click No/Cancel to return to the Save As dialog.

➤ To optimize a fi le in the GIF or JPEG format for Web output,

mercredi 23 novembre 2011

Creating document presets

Creating document presets

If you tend to use the same document size, color mode, or other settings repeatedly in the New dialog, take the time to create a document preset for those settings. Th ereafter, you’ll be able to access your settings via the Preset menu, which will save you startup time as you create new fi les.

To create a document preset:

1. Choose File > New or press Ctrl-N/Cmd-N. Th e New dialog opens.

2. Choose settings, such as the width, height, resolution, color mode, bit depth, background contents,color profi le, and pixel aspect ratio. Ignore any setting that you don’t want to include in the preset; you’ll exclude it from the preset in step 5.

3. Click Save Preset. Th e New Document Preset dialog opens.A

4. Enter a Preset Name.

5. Under Include in Saved Settings, uncheck any New dialog settings that you don’t want included in the preset.

6. Click OK. Your new preset will appear on the Preset menu in the New dialog.

➤ To delete a user-created preset, choose it from the Preset menu, click Delete Preset, then click Yes (this can’t be undone).A

If you tend to use the same document size, color mode, or other settings repeatedly in the New dialog, take the time to create a document preset for those settings. Th ereafter, you’ll be able to access your settings via the Preset menu, which will save you startup time as you create new fi les.

To create a document preset:

1. Choose File > New or press Ctrl-N/Cmd-N. Th e New dialog opens.

2. Choose settings, such as the width, height, resolution, color mode, bit depth, background contents,color profi le, and pixel aspect ratio. Ignore any setting that you don’t want to include in the preset; you’ll exclude it from the preset in step 5.

3. Click Save Preset. Th e New Document Preset dialog opens.A

4. Enter a Preset Name.

5. Under Include in Saved Settings, uncheck any New dialog settings that you don’t want included in the preset.

6. Click OK. Your new preset will appear on the Preset menu in the New dialog.

➤ To delete a user-created preset, choose it from the Preset menu, click Delete Preset, then click Yes (this can’t be undone).A

Resolution and dimensions for the Web

Resolution and dimensions for the Web

Choosing the correct fi le resolution for Web output is a no-brainer: It’s always 72 ppi.

Choosing the correct dimensions for Web output requires a little more forethought, because it depends on how your Photoshop images are ultimately going to be used in the Web page layout. To quickly create a document with the proper dimensions

and resolution for Web output, choose a preset in step 3 at right. To determine a maximum custom size for a Photoshop image to be displayed on a Web page, fi rst estimate how large your user’s browser window is likely to be, then calculate how

much of that window the image is going to fi ll.

Currently, the most common monitor size is 1024 pixels wide by 768 pixels high. Most viewers have their browser window open to a width of approximately 1000 pixels. If you subtract the space occupied by the menu bar, scroll bars, and other

controls in the browser interface, you’re left with an area of up to 800 x 600 pixels; you can use those dimensions as a guideline. If your Photoshop fi le is going to be used as a small element in a Web page layout, you can choose smaller dimensions.

Creating a new, blank document

In these instructions, you will create a new, blank document. You can drag and drop or copy and paste imagery into this document from other fi les,or draw or paint imagery by hand using brushes. Th e images can then be edited with Photoshop commands, such as eff ects and fi lters.

To create a new, blank document:

1. Choose File > New (Ctrl-N/Cmd-N). Th e New dialog opens.A

2. Type a name in the Name fi eld.

3. Do either of the following: Choose a preset size option from one of the three categories on the Preset menu: the Default Photoshop Size; a paper size for commercial and desktop printers; or a screen size for Web, mobile, fi lm, and video output. Next,choose a specifi c size for that preset from the

Size menu.

Choose a unit of measure from the menu next to the Width fi eld; the same unit will be chosen automatically for the Height (or to change the unit for one dimension only, hold down Shift while choosing it). Next, enter custom Width and Height values (or use the scrubby sliders).

4. Enter the Resolution required for your target output device — be it an imagesetter or the Web. For the Web, enter 72; for print output,see our discussion of resolution on page 20.You can use the scrubby slider here, too.

5. Choose a document Color Mode (RGB Color is recommended), then from the adjacent menu,choose 8 bit or 16 bit as the color depth. You can convert the image to a diff erent color mode later, if needed (see “Photoshop document color modes” on pages 3–4).

6. Note the Image Size, which is listed on the right side of the dialog. If you need to reduce that size, you can choose smaller dimensions,a lower resolution, or a lower bit depth.

7. For the Background of the image, choose Background Contents: White or Background

Color; or choose Transparent if you want the bottommost tier of the document to be a layer.(To choose a Background color, see Chapter 11. To learn about layers, see Chapter 8.)

8. Click the Advanced arrowhead, if necessary, to display additional options, then choose a Color Profi le. Th is list of profi les will vary depending

on the document Color Mode.

(Note: you can also assign or change the profi le later in the Edit > Assign Profi le dialog. To learn more about color profi les,) For Web or print output, leave the Pixel Aspect Ratio on the default setting of Square Pixels.For video output, choose an applicable option

9. Click OK. A new, blank document window appears onscreen. To save it, see page 24.

➤ To force the New dialog settings to match those of an existing open document, open the New dialog, then from the bottom of the Preset menu, choose the name of the document that has the desired dimensions.

➤ If the Clipboard contains graphic data (say,that you copied from Adobe Photoshop or Illustrator), the New dialog will automatically display the dimensions of that content.Choosing Clipboard from the Preset menu in the New dialog accomplishes the same thing. If you want to prevent the Clipboard dimensions from displaying, and display the last-used fi le dimensions instead, hold down Alt/Option as

you choose File > New.

Choosing the correct fi le resolution for Web output is a no-brainer: It’s always 72 ppi.

Choosing the correct dimensions for Web output requires a little more forethought, because it depends on how your Photoshop images are ultimately going to be used in the Web page layout. To quickly create a document with the proper dimensions

and resolution for Web output, choose a preset in step 3 at right. To determine a maximum custom size for a Photoshop image to be displayed on a Web page, fi rst estimate how large your user’s browser window is likely to be, then calculate how

much of that window the image is going to fi ll.

Currently, the most common monitor size is 1024 pixels wide by 768 pixels high. Most viewers have their browser window open to a width of approximately 1000 pixels. If you subtract the space occupied by the menu bar, scroll bars, and other

controls in the browser interface, you’re left with an area of up to 800 x 600 pixels; you can use those dimensions as a guideline. If your Photoshop fi le is going to be used as a small element in a Web page layout, you can choose smaller dimensions.

Creating a new, blank document

In these instructions, you will create a new, blank document. You can drag and drop or copy and paste imagery into this document from other fi les,or draw or paint imagery by hand using brushes. Th e images can then be edited with Photoshop commands, such as eff ects and fi lters.

To create a new, blank document:

1. Choose File > New (Ctrl-N/Cmd-N). Th e New dialog opens.A

2. Type a name in the Name fi eld.

3. Do either of the following: Choose a preset size option from one of the three categories on the Preset menu: the Default Photoshop Size; a paper size for commercial and desktop printers; or a screen size for Web, mobile, fi lm, and video output. Next,choose a specifi c size for that preset from the

Size menu.

Choose a unit of measure from the menu next to the Width fi eld; the same unit will be chosen automatically for the Height (or to change the unit for one dimension only, hold down Shift while choosing it). Next, enter custom Width and Height values (or use the scrubby sliders).

4. Enter the Resolution required for your target output device — be it an imagesetter or the Web. For the Web, enter 72; for print output,see our discussion of resolution on page 20.You can use the scrubby slider here, too.

5. Choose a document Color Mode (RGB Color is recommended), then from the adjacent menu,choose 8 bit or 16 bit as the color depth. You can convert the image to a diff erent color mode later, if needed (see “Photoshop document color modes” on pages 3–4).

6. Note the Image Size, which is listed on the right side of the dialog. If you need to reduce that size, you can choose smaller dimensions,a lower resolution, or a lower bit depth.

7. For the Background of the image, choose Background Contents: White or Background

Color; or choose Transparent if you want the bottommost tier of the document to be a layer.(To choose a Background color, see Chapter 11. To learn about layers, see Chapter 8.)

8. Click the Advanced arrowhead, if necessary, to display additional options, then choose a Color Profi le. Th is list of profi les will vary depending

on the document Color Mode.

(Note: you can also assign or change the profi le later in the Edit > Assign Profi le dialog. To learn more about color profi les,) For Web or print output, leave the Pixel Aspect Ratio on the default setting of Square Pixels.For video output, choose an applicable option

9. Click OK. A new, blank document window appears onscreen. To save it, see page 24.

➤ To force the New dialog settings to match those of an existing open document, open the New dialog, then from the bottom of the Preset menu, choose the name of the document that has the desired dimensions.

➤ If the Clipboard contains graphic data (say,that you copied from Adobe Photoshop or Illustrator), the New dialog will automatically display the dimensions of that content.Choosing Clipboard from the Preset menu in the New dialog accomplishes the same thing. If you want to prevent the Clipboard dimensions from displaying, and display the last-used fi le dimensions instead, hold down Alt/Option as

you choose File > New.

vendredi 18 novembre 2011

Calculating the correct fi le resolution

Calculating the correct fi le resolution

Resolution for print If you shoot digital photos, your camera will preserve either all the pixels that are captured as raw fi les or a portion of the pixels that are captured as small, medium, or large JPEG fi les. If you use a scanner to acquire images, you can control the number of pixels the device captures by setting the input resolution in the scanner software.

High-resolution photos contain more pixels, and therefore fi ner details, than low-resolution photos, but they also have larger fi le sizes, take longer to render onscreen, require more processing time to edit, and are slower to print. Low-resolution images, however, look coarse and jagged and lack detailwhen printed. Your fi les should have the minimum resolution to obtain the desired output quality from your intended output device at the desired output size — but not much higher. Th ere are three ways to set the resolution value for your digital fi les.

➤ If you open raw digital or JPEG photos into the Camera Raw dialog, which we highly recommend, you can specify an image resolution there

➤ After opening your fi les into Photoshop, you can change the image resolution in the Image Size dialog

➤ When scanning photos, you’ll set the image resolution using the scanning software for that device.

Th e print resolution for digitized images (from a camera or scanner) is calculated in pixels per inch (ppi). A–C For output to an inkjet (desktop) printer, the fi le resolution should be between 240 and 300 ppi.

Commercial print shops have specifi c requirements for their particular output devices, so it’s important to ask them what resolution and halftone screen frequency settings they’re going to use before choosing a resolution for your fi les. For a grayscale image, the proper resolution will usually be around one-and-a-half times the halftone screen frequency (lines per inch) setting of the output device, or 200 ppi; for a color image, the resolution will be around twice the half tone screen frequency, or 250–350 ppi.

Resolution for print If you shoot digital photos, your camera will preserve either all the pixels that are captured as raw fi les or a portion of the pixels that are captured as small, medium, or large JPEG fi les. If you use a scanner to acquire images, you can control the number of pixels the device captures by setting the input resolution in the scanner software.

High-resolution photos contain more pixels, and therefore fi ner details, than low-resolution photos, but they also have larger fi le sizes, take longer to render onscreen, require more processing time to edit, and are slower to print. Low-resolution images, however, look coarse and jagged and lack detailwhen printed. Your fi les should have the minimum resolution to obtain the desired output quality from your intended output device at the desired output size — but not much higher. Th ere are three ways to set the resolution value for your digital fi les.

➤ If you open raw digital or JPEG photos into the Camera Raw dialog, which we highly recommend, you can specify an image resolution there

➤ After opening your fi les into Photoshop, you can change the image resolution in the Image Size dialog

➤ When scanning photos, you’ll set the image resolution using the scanning software for that device.

Th e print resolution for digitized images (from a camera or scanner) is calculated in pixels per inch (ppi). A–C For output to an inkjet (desktop) printer, the fi le resolution should be between 240 and 300 ppi.

Commercial print shops have specifi c requirements for their particular output devices, so it’s important to ask them what resolution and halftone screen frequency settings they’re going to use before choosing a resolution for your fi les. For a grayscale image, the proper resolution will usually be around one-and-a-half times the halftone screen frequency (lines per inch) setting of the output device, or 200 ppi; for a color image, the resolution will be around twice the half tone screen frequency, or 250–350 ppi.

Working with 16 bits per channel

Working with 16 bits per channel

To get good-quality output from Photoshop, a wide range of tonal values must be captured at the outset. Th e wider the dynamic range of your chosen input device, the fi ner the subtleties of color and shade it can capture. Most advanced amateur and professional digital SLR cameras capture at least 12 bits of accurate data per channel.

Like cameras, scanners range widely in quality:

Consumer-level scanners capture around 10 bits of accurate data per channel, whereas the high-end professional ones capture up to 16 bits of accurate

data per channel.

Shadow areas in particular are notoriously difficult to capture well. But if your camera can capture 12 to 16 bits per channel (or you work with high-resolution scans), you will have a head start, because your fi les will contain an abundance of pixels in all levels of the tonal spectrum. Photoshop can process fi les that are in 8, 16, or32 Bits/Channel mode. All Photoshop commands are available for 8-bit fi les. Most Photoshop commands are available for 16-bit fi les (e.g., on the

Filter menu, the Liquify and Lens Correction fi lters are available, as are some or all of the fi lters on the Blur, Noise, Render, Sharpen, Stylize, and Other submenus, whereas fi lters on the other submenusare not). Too few Photoshop commands are available for 32 Bits/Channel fi les to make such fi les a

practical choice.

Although you can lower the bit depth of your fi les via the Image > Mode submenu, it’s better to keep them in 16 Bits/Channel mode. Th e editing and resampling commands in Photoshop can degrade the image quality, but the extra pixels in 16-bit images make this less of a problem.A–B The tonal adjustment commands in particular, such as Levels and Curves, remove pixel data and alter the distribution of pixels across the tonal spectrum.

Signs of pixel loss from destructive edits will be more visible in a high-end print of an 8-bit image than in a 16-bit image. Because 16-bit images contain an ample number of pixels in all parts of the tonal spectrum at the outset, more tonal values are preserved, and the resulting output is higher quality.

To summarize, these are some basic facts about 16-bit fi les to consider:

➤ Photoshop can open 16-bit fi les in CMYK orRGB mode.

➤ 16-bit fi les can be saved in many formats, suchas Photoshop (.psd), Large Document (.psb),Photoshop PDF (.pdf), PNG (.png), TIFF (.tif),

and JPEG 2000 (.jpf).

➤ From the Mac OS, you can print 16-bit fi les,provided your printer supports 16-bit printing.

➤ For commercial print output, your output service provider may request 8-bit fi les, in which case you will need to convert them after image-editing.

Note: If system or storage limitations prevent you from working with 16-bit images, consider following this two-stage approach: Perform the initial tonal corrections (such as Levels and Curves adjustments) on the 16-bits-per-channel image, then

convert it to 8 bits per channel for further editing.

To get good-quality output from Photoshop, a wide range of tonal values must be captured at the outset. Th e wider the dynamic range of your chosen input device, the fi ner the subtleties of color and shade it can capture. Most advanced amateur and professional digital SLR cameras capture at least 12 bits of accurate data per channel.

Like cameras, scanners range widely in quality:

Consumer-level scanners capture around 10 bits of accurate data per channel, whereas the high-end professional ones capture up to 16 bits of accurate

data per channel.

Shadow areas in particular are notoriously difficult to capture well. But if your camera can capture 12 to 16 bits per channel (or you work with high-resolution scans), you will have a head start, because your fi les will contain an abundance of pixels in all levels of the tonal spectrum. Photoshop can process fi les that are in 8, 16, or32 Bits/Channel mode. All Photoshop commands are available for 8-bit fi les. Most Photoshop commands are available for 16-bit fi les (e.g., on the

Filter menu, the Liquify and Lens Correction fi lters are available, as are some or all of the fi lters on the Blur, Noise, Render, Sharpen, Stylize, and Other submenus, whereas fi lters on the other submenusare not). Too few Photoshop commands are available for 32 Bits/Channel fi les to make such fi les a

practical choice.

Although you can lower the bit depth of your fi les via the Image > Mode submenu, it’s better to keep them in 16 Bits/Channel mode. Th e editing and resampling commands in Photoshop can degrade the image quality, but the extra pixels in 16-bit images make this less of a problem.A–B The tonal adjustment commands in particular, such as Levels and Curves, remove pixel data and alter the distribution of pixels across the tonal spectrum.

Signs of pixel loss from destructive edits will be more visible in a high-end print of an 8-bit image than in a 16-bit image. Because 16-bit images contain an ample number of pixels in all parts of the tonal spectrum at the outset, more tonal values are preserved, and the resulting output is higher quality.

To summarize, these are some basic facts about 16-bit fi les to consider:

➤ Photoshop can open 16-bit fi les in CMYK orRGB mode.

➤ 16-bit fi les can be saved in many formats, suchas Photoshop (.psd), Large Document (.psb),Photoshop PDF (.pdf), PNG (.png), TIFF (.tif),

and JPEG 2000 (.jpf).

➤ From the Mac OS, you can print 16-bit fi les,provided your printer supports 16-bit printing.

➤ For commercial print output, your output service provider may request 8-bit fi les, in which case you will need to convert them after image-editing.

Note: If system or storage limitations prevent you from working with 16-bit images, consider following this two-stage approach: Perform the initial tonal corrections (such as Levels and Curves adjustments) on the 16-bits-per-channel image, then

convert it to 8 bits per channel for further editing.

Buying, and choosing settings for, a digital camera

Buying, and choosing settings for, a digital camera

Buying a digital camera

If you’re shopping for a digital camera, the fi rst step is to fi gure out which model suits your output requirements and, of course, your budget. Two factors to consider in this regard are a camera’s megapixel value and the size of its digital light sensor.

Camera manufacturers usually list the resolution of a model as width and height dimensions in pixels (such as 3000 pixels x 2000 pixels). Multiply the two values, and you’ll arrive at a number in the millions, which is the number of pixels the camera captures in each shot. Th is is known as the camera’s megapixel value. If your camera captures a suffi -cient number of pixels, you’ll be able to print highquality closeups and enlargements of your photos.

Compact, inexpensive “point-and-shoot” cameras off er few or no manual controls and have a resolution of 6 to 10 megapixels. Th ey capture enough detail to produce decent-quality 5" x 7" prints but not larger, and acceptable Web output.

Advanced amateur camera models have a resolution of 8 to 12 megapixels. You can get high-quality 8" x 10" prints from these cameras, and they off er

more manual controls.

Professional camera models (such as digital SLRs) have a resolution of 12 megapixels or higher and can produce high-quality 11" x 14" prints or larger — but they’re costly. More importantly, the digital light sensors in such cameras are larger and more sensitive than those in lesser cameras.

Th ey record more precise detail and produce a higher-quality image, with less visual noise. Highmegapixel cameras with large sensors aren’t for everyone — and not just because of their price tag.

Images with a high megapixel count have larger fi le sizes, take longer to upload from the camera to the computer, and require a larger hard drive for storage.

(See our comparison of megapixels and print size on page 22.) Unless you tend to crop your photos or output large prints, an 8- to 10-megapixel camera will be better suited to your needs.

Aside from the megapixel count and the size of the sensor, make sure the camera you buy can accommodate a wide assortment of lenses.

For more advice about buying a camera, you can visit the website for PC Magazine (pcmag.com) or Macworld (macworld.com). Photography magazine websites are also good sources of information.

Choosing settings in your digital camera

You’ve acquired a camera (congratulations!) — nowyou may want some pointers on how to use it.

To get good-quality photographs, in addition to establishing the right lighting conditions, composing the shot artistically, etc., you need to choose your camera settings wisely. Here are some basic guidelines:

➤ Medium- and high-end digital cameras let you choose an ISO setting, which controls the sensitivity of the camera’s digital sensor to light (and is comparable to fi lm speed in fi lm photography). High ISO settings tend to produce digital noise in low-light areas, so it’s best to choose the lowest ISO setting that still

enables you to get the desired exposure.

➤ Decide whether to have your camera capture the photos in the JPEG format or even better, as unprocessed raw fi les.

➤ Choose a color space for your camera: sRGB for onscreen or Web output, or Adobe RGB for print output.

➤ For JPEG photos, choose a white balance setting that’s appropriate for the lighting conditions in which the photos will be shot; the camera will process the image data based on this setting. For raw fi les, you can ignore the white balance setting, as the images won’t be processed inside the camera.

➤ If your camera has a histogram display, use it to verify that your shot was taken with the correct exposure settings (aperture and shutter speed). In an overexposed image, insuffi cient details are captured in the highlight areas; in

an underexposed image, insuffi cient details are captured in the shadow areas. Photoshop can process and adjust only the details that your camera captures.

Regardless of whether you shoot JPEG or raw photos, most exposure defi ciencies, color casts, and other imaging problems can be corrected via the Camera Raw dialog and then the photo can be further corrected via an assortment of adjustment commands in Photoshop.

Buying a digital camera

If you’re shopping for a digital camera, the fi rst step is to fi gure out which model suits your output requirements and, of course, your budget. Two factors to consider in this regard are a camera’s megapixel value and the size of its digital light sensor.

Camera manufacturers usually list the resolution of a model as width and height dimensions in pixels (such as 3000 pixels x 2000 pixels). Multiply the two values, and you’ll arrive at a number in the millions, which is the number of pixels the camera captures in each shot. Th is is known as the camera’s megapixel value. If your camera captures a suffi -cient number of pixels, you’ll be able to print highquality closeups and enlargements of your photos.

Compact, inexpensive “point-and-shoot” cameras off er few or no manual controls and have a resolution of 6 to 10 megapixels. Th ey capture enough detail to produce decent-quality 5" x 7" prints but not larger, and acceptable Web output.

Advanced amateur camera models have a resolution of 8 to 12 megapixels. You can get high-quality 8" x 10" prints from these cameras, and they off er

more manual controls.

Professional camera models (such as digital SLRs) have a resolution of 12 megapixels or higher and can produce high-quality 11" x 14" prints or larger — but they’re costly. More importantly, the digital light sensors in such cameras are larger and more sensitive than those in lesser cameras.

Th ey record more precise detail and produce a higher-quality image, with less visual noise. Highmegapixel cameras with large sensors aren’t for everyone — and not just because of their price tag.

Images with a high megapixel count have larger fi le sizes, take longer to upload from the camera to the computer, and require a larger hard drive for storage.

(See our comparison of megapixels and print size on page 22.) Unless you tend to crop your photos or output large prints, an 8- to 10-megapixel camera will be better suited to your needs.

Aside from the megapixel count and the size of the sensor, make sure the camera you buy can accommodate a wide assortment of lenses.

For more advice about buying a camera, you can visit the website for PC Magazine (pcmag.com) or Macworld (macworld.com). Photography magazine websites are also good sources of information.

Choosing settings in your digital camera

You’ve acquired a camera (congratulations!) — nowyou may want some pointers on how to use it.

To get good-quality photographs, in addition to establishing the right lighting conditions, composing the shot artistically, etc., you need to choose your camera settings wisely. Here are some basic guidelines:

➤ Medium- and high-end digital cameras let you choose an ISO setting, which controls the sensitivity of the camera’s digital sensor to light (and is comparable to fi lm speed in fi lm photography). High ISO settings tend to produce digital noise in low-light areas, so it’s best to choose the lowest ISO setting that still

enables you to get the desired exposure.

➤ Decide whether to have your camera capture the photos in the JPEG format or even better, as unprocessed raw fi les.

➤ Choose a color space for your camera: sRGB for onscreen or Web output, or Adobe RGB for print output.

➤ For JPEG photos, choose a white balance setting that’s appropriate for the lighting conditions in which the photos will be shot; the camera will process the image data based on this setting. For raw fi les, you can ignore the white balance setting, as the images won’t be processed inside the camera.

➤ If your camera has a histogram display, use it to verify that your shot was taken with the correct exposure settings (aperture and shutter speed). In an overexposed image, insuffi cient details are captured in the highlight areas; in

an underexposed image, insuffi cient details are captured in the shadow areas. Photoshop can process and adjust only the details that your camera captures.

Regardless of whether you shoot JPEG or raw photos, most exposure defi ciencies, color casts, and other imaging problems can be corrected via the Camera Raw dialog and then the photo can be further corrected via an assortment of adjustment commands in Photoshop.

jeudi 17 novembre 2011

Changing color profiles

Changing color profiles

When a fi le’s profi le doesn’t conform to the current working space (Adobe RGB, in our case) or the color profi le is missing altogether, you can use the Assign Profi le command to assign the correct one.You may notice visible color shifts if the color data of the fi le is reinterpreted to conform to the new profi le, but rest assured, the color data in the actual image is preserved. Do keep Preview checked,though, so you can see what you’re getting into.

To change or remove a fi le’s color profi le:

1. With a fi le open in Photoshop, choose Edit >Assign Profi le. If the fi le contains layers, an alert may appear, warning you that the appearance of the layers may change; click OK. The Assign Profi le dialog opens.A

2. Check Preview, then click one of the following:

To remove the color profi le, click Don’t Color Manage Th is Document.

To assign your current working space to the fi le, click Working [document color mode and the name of your chosen working space].If you followed our instructions for color management, you’ve already specifi ed Adobe RGB as the Working RGB space, but you can click this option for any photo that wasn’t shot or scanned using that color space.

To assign a diff erent profi le, click Profi le, then choose a profi le that diff ers from your current working space.

3. Click OK.

Th e Convert to Profi le command lets you preview the conversion of a document to an assortment of output profi les and intents, and then converts the color data to the chosen profi le.

Note: Th is command performs a mode conversion and changes the actual color data in your fi le!

To convert a fi le’s color profi le:

1. Choose Edit > Convert to Profi le. In the Convert to Profi le dialog,B check Preview.

2. Under Destina tion Space, from the Profi le menu, choose the profi le you want to convert the fi le to (it doesn’t necessarily have to be the current working space).

3. Under Conversion Options, choose an Intent(for the intents, see the sidebar on page 405).

4. Leave the default Engine as Adobe (ACE) and keep Use Black Point Compensation and Use Dither checked.

5. Optional: Check Flatten Image to Preserve Appearance to merge all layers and adjustment layers in the document.

6. Click OK

Acquiring printer profiles

Acquiring printer profiles

Th us far, we’ve shown you how to set your camera to the Adobe RGB color space, calibrate your display, and specify Adobe RGB as the color space for Photoshop. Next you’ll learn how to acquire the proper printer profi le(s) so you can incorporate color management into your specifi c printing

scenario.

To download the printer profi le for an inkjet printer:

Most printer manufacturers have a website from which you can download either an ICC profi le for a specifi c printer/paper combination or a printer driver that contains a collection of specifi c ICC printer/paper profi les. Be sure to choose a profi le that conforms to the particular printer/paper combination you will be using.

1. On the following page, we step you through a few pages on the websites for two manufacturers of widely used printers: Epson, focusing on the Stylus Photo R series (Epson.com) (A–C, next page) and Canon (Canon.com) (D–F, next page).

Another option is to also download an ICC profi le for a specifi c printer/paper combo from the website for a paper manufacturer, such as ilford.com or crane.com/museo.

Note: Th e profi les for the newest printer models may not be available yet on these sites. Check back periodically.

2. After visiting the website, install the profi le you downloaded by following the instructions that

accompany it. On pages 404–405, we’ll show you how to use the profi le to soft-proof a document onscreen.

Saving custom color settings

Saving custom color settings

For desktop color printing, we recommended choosing North America Prepress 2 as the color setting for Photoshop (see page 10). For commercial printing, let the pros supply the proper color settings: Ask your print shop to send you a .csffi le with all the correct Working Spaces and Color Management Policies settings for their particular press. Th en all you’ll need to do is install that custom color settings fi le in the proper location by following the instructions below and, when needed, choose it from the Settings menu in the Color Settings dialog.

To save custom color settings as defaults for the Creative Suite:

1. In Windows, put the fi le in Program Files\Common Files\ Adobe \Color\Settings.

In the Mac OS, put the fi le in Users/[user name]/Library/Application Support/ Adobe/Color/Settings.

2. To access the newly saved settings fi le, open the Color Settings dialog, then choose the name of the .csf fi le from the Settings menu. If your print shop gives you a list of recommended settings for the Color Settings dialog — but not an actual .csf fi le — you can choose and then save that collection of settings as a .csf fi le by following theseinstructions.

To save custom color settings:

1. Choose Edit > Color Settings (Ctrl-Shift-K/Cmd-Shift-K). Th e Color Settings dialog opens.

2. Enter the required settings by choosing and checking the appropriate options.

3. Click Save and enter a fi le name (we recommend including the printer type in the name),keep the .csf extension and the default location, then click Save.

4. Click OK to exit the Color Settings dialog.

For desktop color printing, we recommended choosing North America Prepress 2 as the color setting for Photoshop (see page 10). For commercial printing, let the pros supply the proper color settings: Ask your print shop to send you a .csffi le with all the correct Working Spaces and Color Management Policies settings for their particular press. Th en all you’ll need to do is install that custom color settings fi le in the proper location by following the instructions below and, when needed, choose it from the Settings menu in the Color Settings dialog.

To save custom color settings as defaults for the Creative Suite:

1. In Windows, put the fi le in Program Files\Common Files\ Adobe \Color\Settings.

In the Mac OS, put the fi le in Users/[user name]/Library/Application Support/ Adobe/Color/Settings.

2. To access the newly saved settings fi le, open the Color Settings dialog, then choose the name of the .csf fi le from the Settings menu. If your print shop gives you a list of recommended settings for the Color Settings dialog — but not an actual .csf fi le — you can choose and then save that collection of settings as a .csf fi le by following theseinstructions.

To save custom color settings:

1. Choose Edit > Color Settings (Ctrl-Shift-K/Cmd-Shift-K). Th e Color Settings dialog opens.

2. Enter the required settings by choosing and checking the appropriate options.

3. Click Save and enter a fi le name (we recommend including the printer type in the name),keep the .csf extension and the default location, then click Save.

4. Click OK to exit the Color Settings dialog.

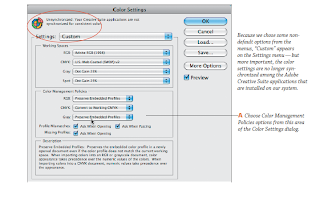

Customizing your color policies

Customizing your color policies

Th e current color management policies govern whether Photoshop honors or overrides a document’s settings if the color profi le in the fi le, when opened or imported, doesn’t conform to the current color settings in Photoshop. If you chose the North

America Prepress 2 setting in the Color Settings dialog (page 10), the Ask When Opening policy (the safest option, in our opinion) is already chosen for you, and you can skip these instructions.

To customize the color management policies for Photoshop:

1. Choose Edit > Color Settings (Ctrl-Shift-K/Cmd-Shift-K). Th e Color Settings dialog opens.A

2. From the Color Management Policies menus,choose an option for fi les that are to be opened or imported into Photoshop:

Off to prevent Photoshop from color-managing the fi les. Preserve Embedded Profi les if you expect to work with both color-managed and non-colormanaged documents, and you want each fi le to keep its own profi le.Convert to Working RGB or Convert to Working CMYK to have all documents that you open or import into Photoshop adopt the program’s current color working space. Th is is usually the best choice for Web output.

3. Do any of the following optional steps:

For Profi le Mismatches, if you check Ask When Opening, Photoshop will display an

alert if the color profi le in a fi le you’re opening doesn’t match the current working space.

Via the alert, you will be able to override the current color management policy for each fi le.Check Ask When Pasting to have Photo shop display an alert if it encounters a color profi le mismatch when you paste or drag and drop color imagery into a document. Th e alert lets you override your color management policy when pasting.

For fi les with Missing Profi les, check Ask When Opening to have Photoshop display an alert off ering an option to assign a profi le.

4. Click OK.

Th e current color management policies govern whether Photoshop honors or overrides a document’s settings if the color profi le in the fi le, when opened or imported, doesn’t conform to the current color settings in Photoshop. If you chose the North

America Prepress 2 setting in the Color Settings dialog (page 10), the Ask When Opening policy (the safest option, in our opinion) is already chosen for you, and you can skip these instructions.

To customize the color management policies for Photoshop:

1. Choose Edit > Color Settings (Ctrl-Shift-K/Cmd-Shift-K). Th e Color Settings dialog opens.A

2. From the Color Management Policies menus,choose an option for fi les that are to be opened or imported into Photoshop:

Off to prevent Photoshop from color-managing the fi les. Preserve Embedded Profi les if you expect to work with both color-managed and non-colormanaged documents, and you want each fi le to keep its own profi le.Convert to Working RGB or Convert to Working CMYK to have all documents that you open or import into Photoshop adopt the program’s current color working space. Th is is usually the best choice for Web output.

3. Do any of the following optional steps:

For Profi le Mismatches, if you check Ask When Opening, Photoshop will display an

alert if the color profi le in a fi le you’re opening doesn’t match the current working space.

Via the alert, you will be able to override the current color management policy for each fi le.Check Ask When Pasting to have Photo shop display an alert if it encounters a color profi le mismatch when you paste or drag and drop color imagery into a document. Th e alert lets you override your color management policy when pasting.

For fi les with Missing Profi les, check Ask When Opening to have Photoshop display an alert off ering an option to assign a profi le.

4. Click OK.

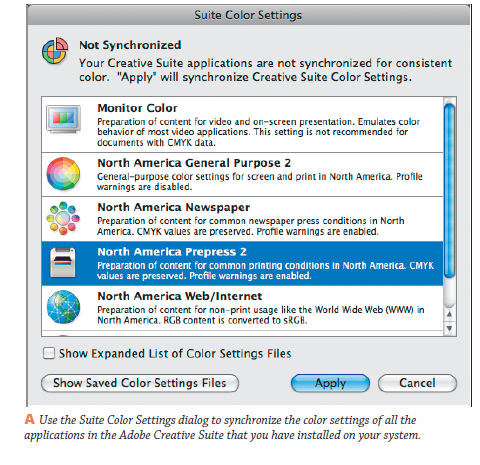

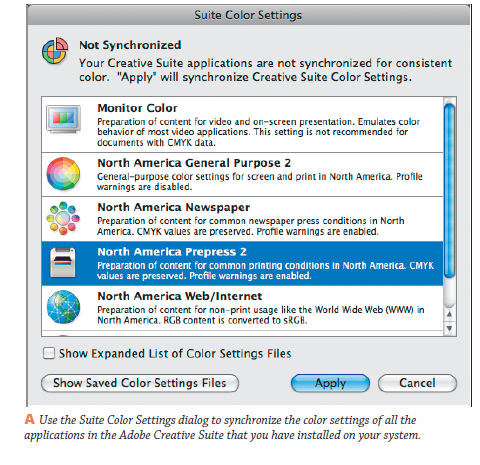

Synchronizing color settings

Synchronizing color settings

If the color settings in another Adobe Creative Suite program that you have installed on your system (such as Illustrator or InDesign) don’tmatch the settings in Photoshop, an alert will display at the top of the Color Settings dialog (as in A, next page). If you haven’t installed one of the full Adobe Creative Suites, you’ll have to start up the errant application and fi x its color settings by hand. If you do have a suite installed, you can use the Suite Color Settings dialog in Bridge to synchronize the color settings for all of the colormanaged Adobe programs on your system Before synchronizing the color settings via Bridge, make sure you’ve chosen the proper settings inPhotoshop (see the preceding two pages).

1. On the Application bar in Photoshop, click the Launch Bridge button.

2. In Bridge, choose Edit > Creative Suite Color Settings (Ctrl-Shift-K/Cmd-Shift-K). Th e Suite Color Settings dialog opens.A

3. Click the same settings preset you chose in the Color Settings dialog in Photoshop, then click Apply. Bridge will change (synchronize) the color settings of the other Adobe Creative Suite applications to conform to the selected preset

If the color settings in another Adobe Creative Suite program that you have installed on your system (such as Illustrator or InDesign) don’tmatch the settings in Photoshop, an alert will display at the top of the Color Settings dialog (as in A, next page). If you haven’t installed one of the full Adobe Creative Suites, you’ll have to start up the errant application and fi x its color settings by hand. If you do have a suite installed, you can use the Suite Color Settings dialog in Bridge to synchronize the color settings for all of the colormanaged Adobe programs on your system Before synchronizing the color settings via Bridge, make sure you’ve chosen the proper settings inPhotoshop (see the preceding two pages).

To synchronize the color settings among Creative Suite applications using Bridge:

1. On the Application bar in Photoshop, click the Launch Bridge button.

2. In Bridge, choose Edit > Creative Suite Color Settings (Ctrl-Shift-K/Cmd-Shift-K). Th e Suite Color Settings dialog opens.A

3. Click the same settings preset you chose in the Color Settings dialog in Photoshop, then click Apply. Bridge will change (synchronize) the color settings of the other Adobe Creative Suite applications to conform to the selected preset

Choosing a color space for Photoshop

Choosing a color space for Photoshop

Continuing with our recommended steps for color management, you’ll use the Color Settings dialog to set the color space for Photoshop. If you want to get up and running quickly by establishing Adobe RGB as the color space without wading through all the options in the Color Settings dialog, you can make one simple preset choice by following the fi rst set of instructions below — that is, if you use the program primarily to produce images for print output on a commercial or color inkjet printer and you’ve followed our instructions for color management thus far.

To choose a color settings preset:

1. Choose Edit > Color Settings (Ctrl-Shift-K/Cmd-Shift-K). Th e Color Settings dialog opens(A, next page).

2. Choose Settings: North America Prepress 2readers residing outside North America,

choose an equivalent for your output device and geographic location). Th is preset changes the RGB working space to Adobe RGB (1998),and sets all the color management policies to the safe choice of Preserve Embedded Profi les so each fi le you open in Photoshop will keep its own profi le.

3. Click OK.

If you want to explore the Color Settings dialog in more depth, follow these instructions instead. Pick and choose among the options, depending on your

output requirements.

To choose color settings options:

1. Choose Edit > Color Settings (Ctrl-Shift-K/Cmd-Shift-K). Th e Color Settings dialog opens(A, next page).

2. From the Settings menu, choose one of these presets, depending on your output needs:

Monitor Color sets the RGB working space to your display profi le. Th is is a good choice for video output, but not for print output.

North America General Purpose 2 meets the requirements for screen and print output in North America. All profi le warnings are off .North America Newspaper manages color for output on newsprint paper stock.North America Prepress 2 manages color to

conform with common press conditions in North America. Th e default RGB color space

that is assigned to this setting is Adobe RGB.

When CMYK documents are opened, their values are preserved.

North America Web/Internet is designed for online output. All RGB images are converted to the sRGB color space.

3. Th e Working Spaces settings control how RGB and CMYK colors are treated in a document that lacks an embedded profi le. You can either leave these settings as they are or choose other options (the RGB options are discussed below).

For the CMYK setting, ask your output service provider which working space to choose.

We recommend choosing one of these RGB color spaces, depending on your output needs:

Monitor RGB [current display profi le] sets the RGB working space to your display profi le, and is useful if you know that other applications you’ll be using for your project don’t support color management. Keep in mind, however,that if you share fi les that use your monitor profi le (as the color space) with another user,

their monitor profi le will be substituted for the RGB working space, and this may undermine the color consistency that you’re aiming for.ColorSync RGB (Mac OS only) matches the Photoshop RGB space to the space that’s specifi ed in the Apple ColorSync Utility. If you share this confi guration with another user, it will use the ColorSync space that’s specifi ed in their system.

Adobe RGB 1998 contains a wide range of colors and is useful when converting RGB

images to CMYK. You may have gotten our drift by now that this option is recommended for print output but not for online output.

ProPhoto RGB contains a very wide range of colors and is useful for output to high-end inkjet and dye sublimation printers.sRGB IEC619662.1 is a good choice for Web

output, as it refl ects the settings on the average computer display. Many hardware and software manufacturers use this as the default space forscanners, low-end printers, and software.

4. Click OK.

➤ Th e Adobe RGB (1998) color space, which is recommended for print output, includes more colors in the printable CMYK gamut than the sRGB IEC61966-2.1 color space, which is designed for online output. Although sRGB IEC61966-2.1 is the default listing on the Working Spaces: RGB menu in the Color Settings dialog, it can spell disaster for print output.

Continuing with our recommended steps for color management, you’ll use the Color Settings dialog to set the color space for Photoshop. If you want to get up and running quickly by establishing Adobe RGB as the color space without wading through all the options in the Color Settings dialog, you can make one simple preset choice by following the fi rst set of instructions below — that is, if you use the program primarily to produce images for print output on a commercial or color inkjet printer and you’ve followed our instructions for color management thus far.

To choose a color settings preset:

1. Choose Edit > Color Settings (Ctrl-Shift-K/Cmd-Shift-K). Th e Color Settings dialog opens(A, next page).

2. Choose Settings: North America Prepress 2readers residing outside North America,

choose an equivalent for your output device and geographic location). Th is preset changes the RGB working space to Adobe RGB (1998),and sets all the color management policies to the safe choice of Preserve Embedded Profi les so each fi le you open in Photoshop will keep its own profi le.

3. Click OK.

If you want to explore the Color Settings dialog in more depth, follow these instructions instead. Pick and choose among the options, depending on your

output requirements.

To choose color settings options:

1. Choose Edit > Color Settings (Ctrl-Shift-K/Cmd-Shift-K). Th e Color Settings dialog opens(A, next page).

2. From the Settings menu, choose one of these presets, depending on your output needs:

Monitor Color sets the RGB working space to your display profi le. Th is is a good choice for video output, but not for print output.

North America General Purpose 2 meets the requirements for screen and print output in North America. All profi le warnings are off .North America Newspaper manages color for output on newsprint paper stock.North America Prepress 2 manages color to

conform with common press conditions in North America. Th e default RGB color space

that is assigned to this setting is Adobe RGB.

When CMYK documents are opened, their values are preserved.

North America Web/Internet is designed for online output. All RGB images are converted to the sRGB color space.

3. Th e Working Spaces settings control how RGB and CMYK colors are treated in a document that lacks an embedded profi le. You can either leave these settings as they are or choose other options (the RGB options are discussed below).

For the CMYK setting, ask your output service provider which working space to choose.

We recommend choosing one of these RGB color spaces, depending on your output needs:

Monitor RGB [current display profi le] sets the RGB working space to your display profi le, and is useful if you know that other applications you’ll be using for your project don’t support color management. Keep in mind, however,that if you share fi les that use your monitor profi le (as the color space) with another user,

their monitor profi le will be substituted for the RGB working space, and this may undermine the color consistency that you’re aiming for.ColorSync RGB (Mac OS only) matches the Photoshop RGB space to the space that’s specifi ed in the Apple ColorSync Utility. If you share this confi guration with another user, it will use the ColorSync space that’s specifi ed in their system.

Adobe RGB 1998 contains a wide range of colors and is useful when converting RGB

images to CMYK. You may have gotten our drift by now that this option is recommended for print output but not for online output.

ProPhoto RGB contains a very wide range of colors and is useful for output to high-end inkjet and dye sublimation printers.sRGB IEC619662.1 is a good choice for Web

output, as it refl ects the settings on the average computer display. Many hardware and software manufacturers use this as the default space forscanners, low-end printers, and software.

4. Click OK.

➤ Th e Adobe RGB (1998) color space, which is recommended for print output, includes more colors in the printable CMYK gamut than the sRGB IEC61966-2.1 color space, which is designed for online output. Although sRGB IEC61966-2.1 is the default listing on the Working Spaces: RGB menu in the Color Settings dialog, it can spell disaster for print output.

mercredi 16 novembre 2011

Calibrating your display

Calibrating your display

Display types

Th ere are two main types of computer displays: a CRT (cathode ray tube, as in a traditional TV set) and the more common LCD (liquid crystal display,or fl at panel display). Th e display performance of a CRT fl uctuates due to its analog technology and the fact that its display phosphors (which produce the glowing dots that you see onscreen) fade over time. A CRT display can be calibrated reliably for

only around three years.

LCD displays use a grid of fi xed-sized liquid crystals that fi lter color coming from a back light source. Although you can adjust only the brightness on an LCD (not the contrast), the LCD digital technology off ers more reliable color consistency than a CRT, without the characteristic fl ickering of a CRT. Th e newest LCD models provide good viewing angles, display accurate color, use the desired daylight temperature of 6500K for the white point (see below), and are produced under tighter manufacturing standards than CRTs. Moreover, the color profi le that’s provided with an LCD display (and that is installed in your system automatically) usually describes the display characteristics accurately.

➤ Both types of displays lose calibration gradually, and you may not notice the change until the colors are way off . To maintain the color consistency of your display, stick to a regular monthly calibration schedule. Thankfully,our calibration software reminds us to recalibrate our display via a monthly onscreen alert.

Understanding the calibration settings

Th ree basic characteristics are adjusted when a display is calibrated: Th e brightness (white level) is set to a consistent working standard; the contrast (dark level) is set to the maximum value; and a neutral gray (gray level) is established using equal values of R, G, and B. To adjust these characteristics,calibration devices evaluate the white point,black point, and gamma in the display.

➤ Th e white point data enables the display to project a pure white, which matches

an industry-standard color temperature.Photographers favor using D65/6500K as the

temperature setting for the white point.

➤ Th e black point is the darkest black a display can project. All other dark shades are lighter than this darkest black, which ensures that shadow details display properly.

➤ Th e gamma defi nes how midtones are displayed onscreen. A gamma setting of 1.0 reproduces the linear brightness scale that is found in nature. Human vision, however, responds to brightness in a nonlinear fashion, so this setting makes the screen look washed out. A higher gamma setting redistributes more of the midtones into the dark range, which our eyes are more sensitive to, and produces a more natural-looking image. Photography experts recommend using a gamma setting of 2.2 for both Windows and Macintosh displays.

Buying a calibration device

Th e only way to calibrate a display properly is by using a hardware calibration device, which produces a profi le containing the proper white point,black point, and gamma settings for your display.Th e Adobe color management system, in turn, will use that profi le to display colors in your Photoshop document more accurately.

If you’re shopping for a calibration device,you’ll notice a wide range in cost, from a $100 to $300 colorimeter to a much more costly, but more precise, high-end professional gadget, such as a spectrophotometer. A colorimeter and its stepby-step wizard tutorial will enab e you to calibrate your display more precisely than you could by using subjective “eyeball” judgments. Among moderately priced calibrators, our informal reading of hardware reviews and other industry publications has yielded the following as some of the current favorites: Spyder3Pro and Spyder3Elite by Datacolor; i1 Display 2 and i1 Display LT by X-Rite; and hueyPro, which was

developed jointly by PANTONE and X-Rite.

Note: If, after calibrating your display, you intentionally or unintentionally adjust the display’s brightness and contrast settings or change the room lighting (or repaint your walls!), remember to recalibrate it!

For Mac OS users who don’t have a calibration device, your system supplies a display calibration utility; look for it in System Preferences > Displays > Color. Click Calibrate and follow the instructions that appear onscreen.

Th e steps outlined here apply loosely to the three hardware display calibrators that are mentioned on the preceding page. We happen to use Spyder3Pro.

To calibrate your display using a hardware device:

1. Set the room lighting to the level that you normally use for work. If you have a CRT, let it warm up for 30 minutes for the display to stabilize.

2. Increase the brightness of your display to its highest level. In the Mac OS, if you have an Apple display, choose System Preferences > Displays and drag the Brightness slider to the far right. For a third-party display or any Windows display, use either a mechanical button on the display or a menu command in the OnScreen Display (OSD).

3. Launch the calibration application that you’ve installed, then follow the straightforward instructions on the step-by-step wizard screens.A–B You will need to tell the application the following important information: your display type (CRT or LCD), the white point to be used (choose D65/6500K), and the desired gamma value

(choose 2.2 for both Windows and Macintosh).

For a CRT display, you may see a few more instructional screens requesting further display setting choices.

4. After entering your display information (A,next page), you’ll be prompted to drape the colorimeter(hardware calibration sensor) over the monitor (B, next page). For an LCD, if a baffl e is included with the calibration device, clip it on to prevent the suction cups from touching and potentially damaging the screen. Follow the instructions to align the sensor with the image onscreen. Click OK or Continue to initiate the series of calibration tests, which will take from 5 to 8 minutes.

5. After removing the calibration sensor, you’ll be prompted to name your new display profi le (C, next page). Include the date in the profi le name, for your own reference. Th e application will place the new profi le in the correct location

for your Windows or Macintosh operating system. Th e wizard will step you through one or two more screens, and then you’re done. When launched, Photoshop will automatically be aware of the new display profile.

c

Setting a camera’s color space to Adobe RGB

Setting a camera’s color space to Adobe RGB

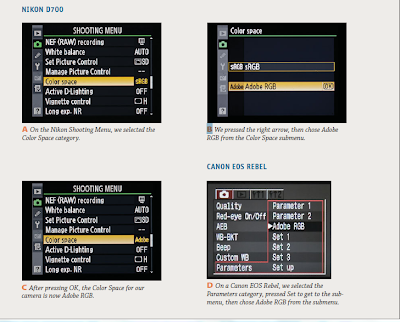

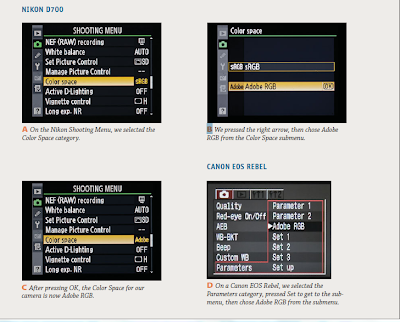

Most high-end, advanced amateur digital cameras and digital SLR cameras have an onscreen menu, which you can use to customize how the camera processes digital images. Although we’ll use a Nikon D700 as our representative model for setting a camera to the Adobe RGB color space, you can follow a similar procedure to set the color space for your camera. Note: If you shoot photos in the JPEG format,you should choose Adobe RGB as the color space for your camera, regardless of which model it is. If you shoot raw fi les, these steps are optional, as you will have the opportunity to assign the Adobe RGB color space when you convert your photos via the Camera Raw plug-in

To set a camera’s color space to Adobe RGB:

1. On the back of your Nikon camera, press the Menu button to access the menu on the LCD screen, and then, if necessary, press the up or down arrow on the multi selector to select the Shooting Menu tab.

2. On the Shooting Menu, press the down arrow on the multi selector to select the Color Space category A (Canon EOS Rebel cameras label this category as Parameters). Press the right arrow on the multi selector to move to the submenu.

3. Press the down arrow to select Adobe RGB.B

4. Press the OK button to set your choice,C–D then press the Menu button to exit the Menu screen. B

Most high-end, advanced amateur digital cameras and digital SLR cameras have an onscreen menu, which you can use to customize how the camera processes digital images. Although we’ll use a Nikon D700 as our representative model for setting a camera to the Adobe RGB color space, you can follow a similar procedure to set the color space for your camera. Note: If you shoot photos in the JPEG format,you should choose Adobe RGB as the color space for your camera, regardless of which model it is. If you shoot raw fi les, these steps are optional, as you will have the opportunity to assign the Adobe RGB color space when you convert your photos via the Camera Raw plug-in

To set a camera’s color space to Adobe RGB:

1. On the back of your Nikon camera, press the Menu button to access the menu on the LCD screen, and then, if necessary, press the up or down arrow on the multi selector to select the Shooting Menu tab.

2. On the Shooting Menu, press the down arrow on the multi selector to select the Color Space category A (Canon EOS Rebel cameras label this category as Parameters). Press the right arrow on the multi selector to move to the submenu.

3. Press the down arrow to select Adobe RGB.B

4. Press the OK button to set your choice,C–D then press the Menu button to exit the Menu screen. B

Introduction to color management

Introduction to color management

Problems with color inconsistency can arise due to the fact that hardware devices and software packages read or output color diff erently. If you were to compare how an image looks in an assortment of imaging programs and Web browsers, the colors might look completely diff erent in each case, and worse still, may not match the picture you originally shot with your digital camera. Print the image, and you’ll probably fi nd the results are different yet again. In some cases, these diff erences might be slight and unobjectionable, but in other cases such color shifts can wreak havoc with your design or turn a project into a disaster! A color management system can prevent most color discrepancies by acting as a color interpreter. It knows how each particular device and program interprets color, and adjusts those colors when necessary. Th e result is that the colors in your fi les will display and output more consistently as the fi les are shuttled among various programs and devices. Applications in Adobe Creative Suite 5 use standardized ICC (International Color Consortium)profi les, which tell your color management system how each specifi c device defi nes color. Each particular device ca n capture and reproduce only a limited range (gamut) of colors, which in the jargon of color management is known as the color space. Th e mathematical description of the color space of each device, in turn, is called its color profi le. Furthermore, each input device, such as a camera, attaches its own profi le to the fi les it produces. Photoshop will use that profi le in order to display and edit the colors in your document;or if the document doesn’t contain a profi le,Photoshop will use the current working space (a color space you choose for Photoshop) instead. Color management is especially important when the same image is used for multiple purposes, such as for online output and print output. Note: For print output, be sure to consult with your prepress service provider or commercial printer (if you’re using one) about color management to ensure that your color management setup works smoothly with theirs. Th e “meat” of this chapter consists of instructions for choosing color management options, which we strongly recommend you follow before editing your images in Photoshop. Our instructions are centered on using Adobe RGB as the color space for your image-editing work to create color consistency throughout your workfl ow. We’ll show you how to set the color space of your digital camera to Adobe RGB, calibrate your display, specify Adobe RGB as the color space for Photoshop, acquire the proper profi les for your inkjet printer and paper type, and assign Adobe RGB as the profi le of choice for fi les that don’t use that color space. You’ll need to focus on color management again when you prepare your fi le for printing. In Chapter 25 (Print), you will create a soft-proof setting for your particular inkjet printer and paper using the acquired profi les, and then use it to view a soft proof of your document onscreen. Th e profi le willalso be used for outputting fi les to a color inkjet printer, a device that expects fi les to be in RGB color. Finally, we’ll show you how to use the appropriate profi les when outputting either to the Web or to a commercial press. Th e fi rst step in color management is to establish Adobe RGB as the color space for your camera.